Mindful Investing: Escaping the Trap of “Emotional Thinking”

In a book recounting how he became one the world’s richest men, George Soros describes how investor beliefs create market bubbles – illusions of value – that keep on growing, until they ultimately burst, causing a market crash. According to Soros, market bubbles happen when investors fail to realize that a particular asset (real estate, currency, stock, or whatever) is going up in price, not because of any real value, but simply because everyone’s been buying it.

In a book recounting how he became one the world’s richest men, George Soros describes how investor beliefs create market bubbles – illusions of value – that keep on growing, until they ultimately burst, causing a market crash. According to Soros, market bubbles happen when investors fail to realize that a particular asset (real estate, currency, stock, or whatever) is going up in price, not because of any real value, but simply because everyone’s been buying it.

A classic example was the real estate bubble that collapsed in 2008. Easy credit led to increased home buying (demand), which in turn led to higher real estate valuations, which in turn made more people frantic to “jump on the band wagon.” Another example, even closer to home for Soros, was the rising price of the British pound sterling in the early 1990’s. Soros saw that the pound was being propped up with borrowed money and was way overvalued. Realizing this “bubble” would burst, Soros executed a short sale on $10 billion worth of pounds on September 16, 1992, realizing $1 billion in profits in a single day.

In his book, Soros describes an earlier personal turning point back in the mid-1980s, when he decided to confront his own biases by keeping a diary. In the diary, he would write down his reasoning behind each trade, noting carefully when his predictions worked and when they failed. In this way, he sought to more rigorously test his personal theories and learn to become more objective. This practice, he believed, prepared him for later trading successes.

The Trap of “Emotional Thinking”

It’s long been known that strongly held values and beliefs can filter and bias our perceptions. As early as the 1940s, a study by Indiana University psychologist Leo Postman and colleagues revealed that people more quickly recognize words related to their personal values, and make more mistakes when reading words contrary to their values.

Another way that values and beliefs distort our reality is through the confirmation bias, a tendency to twist and filter facts to make them fit existing beliefs. One of the best-researched sources of judgment errors, confirmation bias narrows our field of attention to facts, filters out evidence that doesn’t fit existing beliefs, and overweights evidence that does. Studies have shown that even  scientists are susceptible to confirmation bias, prompting them to more readily believe weak evidence supporting established theories, and to suspect that investigators who disconfirm mainstream theories must be using inferior research methods or committing mistakes.

scientists are susceptible to confirmation bias, prompting them to more readily believe weak evidence supporting established theories, and to suspect that investigators who disconfirm mainstream theories must be using inferior research methods or committing mistakes.

And it’s not just our values and beliefs that bias our judgments. Recent research reveals that past decisions or actions also create a sense of emotional commitment that greatly distorts our judgments of value – that is, what we believe something is worth. The simplest example of this is what Cornell’s Richard Thaler calls the endowment effect. In a typical experiment, people estimate what they would pay for a particular item, say, a coffee mug or bottle of wine. Then they’re asked what they would accept for the same item if they already owned it and were asked to sell it. Typically, already owning something causes people to ask several times the amount they would have paid for it. Thus, it seems that owning a thing strengthens an emotional bond with the item and inflates perceptions of worth.

An especially dangerous form of endowment effect is the sunk cost bias or the “tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made.” In other words, once we’ve spent resources on something – like a losing strategy or doomed investment – we stubbornly hold on to it, even when warning signs are telling us to abandon ship. Research on thousands of trades at a large discount brokerage house have shown this bias to be a significant source of loss for investors.

Sunk cost bias has effects far greater and more insidious than staying too long with stock market losers. It can also lead to major  misfortunes like disastrous military campaigns and overbudget public works projects. The more lives lost, the more assets expended, the more urgently we feel a need to “stay the course” and justify prior sacrifices. No one wants to proclaim failure and “pull the plug.”

misfortunes like disastrous military campaigns and overbudget public works projects. The more lives lost, the more assets expended, the more urgently we feel a need to “stay the course” and justify prior sacrifices. No one wants to proclaim failure and “pull the plug.”

Sunk cost bias and confirmation bias would not be so dangerous, if we only knew when they were present and could work to counter them by examining evidence to the contrary. But the problem is that, like barnacles on one side of a ship’s rudder, these biases operate below the surface, steering us off center, without our conscious awareness. So, people think they’re acting rationally, based on the best available evidence, but in fact, they’re showing what Harvard Psychologist Ellen Langer calls mindless automaticity. In effect, they’re on “automatic pilot”, acting on emotion and ignoring signals that should make them choose more wisely. The result is a kind of forced overconfidence that leads to long-term losses.

Overcoming Emotional Thinking

So how do we avoid this automatic emotional thinking that inclines us toward past decisions and warps our view of present options? To make better decisions, we first need to get off autopilot and pay close attention to all available information, including our own emotional signals. Like a pilot heading into bad weather, we can’t be mulling over past mistakes or what we’ll say when we wave good-bye to passengers at the gate. We need to focus on what’s happening right now.

So while our gut feelings may be one kind of signal, we must also pay attention to changing conditions and respond to important information inputs. For the pilot, this means scanning the horizon, watching instruments, and noting weather conditions in different directions and at different altitudes. By the same token, investors should be alert to changing market trends and gathering relevant facts for each investment option.

Now it’s unrealistic to think we can eliminate all forms of bias in our decision-making, but there are some steps to mitigate it, based upon decision research. These include the following:

1. Analyze and compare multiple options. Research has shown that people are much better at comparing strengths and weaknesses of multiple options than they are at evaluating a single option in isolation. So it makes sense to always have at least two alternatives in mind. This means you shouldn’t just think “to sell or not to sell”, but rather, “If I did sell, is there a better place to put the proceeds?” In other words, your array of options should include at least one solid Plan B. This is tough to do in practice because it makes the options more balanced and the choice more difficult. But it’s likely to result in a less biased decision.

2. Before you decide, practice mindful self-awareness. This sounds like a new age nostrum, but is really based in science. Andrew Hafenbrack, and his colleagues at Wharton School of Business report a series of four studies on sunk cost bias encompassing almost 500 adults. In the studies, they found that a 15-minute mindfulness exercise (focused-breathing meditation) enabled more than three quarters of their subjects to resist sunk cost bias in a subsequent decision, versus fewer than half of control subjects who didn’t do the exercise. Moreover, the mindfulness-trained subjects showed more focused awareness of both the present moment and their own physical sensations. Self-awareness was also proven to be pivotal in a study of London investment bankers, cited by emotional intelligence guru Dan Goleman. It that study, encompassing four banks, 128 traders and senior managers, everyone used analytical tools. But the more self-aware traders also attended to a wider array of emotional signals – including their own anxiety – telling them when to invest and when to hold back. As a result, earnings of the more “mindful” investors averaged five times greater than their less self-aware colleagues.

3. Stay open-minded. Consult with people who’ll tell you things you don’t already know. It’s critical to source information about alternatives from range of unbiased providers – people with no stake in the transaction. To make good

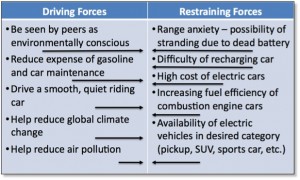

It’s natural to feel anxiety and desire closure when facing a big decision, and yet this very tendency to avoid discomfort is what can push us into a bias-land, if we’re not careful. A helpful attitude during your information-gathering phase is tolerance for ambiguity or the ability to hold conflicting views in mind. Ambiguity tolerance prevents premature closure and has been found to be hallmark of successful entrepreneurs and investment bankers. A simple aid in keeping the mind open is to list pluses and minuses (or benefits and risks) for each option. Feelings, hunches, or intuitions can be included in this list, on whatever side of the ledger they belong. But the main idea is that by writing everything down – including emotional reactions – we raise awareness and reduce the odds of hidden influences on our choices.

*****

Readers who wish to learn more about investment decision-making are encouraged to check out this article by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and colleagues, or this very thorough book by Harvard Professor Max Bazerman. Also, you can check out this reading list on Mindful Investing.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stanford psychologist

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stanford psychologist

This bias for the short-term has led Christensen and van Bever to label spreadsheets as the “fast food of strategic decision making.” So just as fast food helped to create an obesity epidemic through overconsumption of high-calorie comfort food, management-by-spreadsheet has created an over reliance upon investments in short-term efficiency improvement, undermining the long-term health of businesses.

This bias for the short-term has led Christensen and van Bever to label spreadsheets as the “fast food of strategic decision making.” So just as fast food helped to create an obesity epidemic through overconsumption of high-calorie comfort food, management-by-spreadsheet has created an over reliance upon investments in short-term efficiency improvement, undermining the long-term health of businesses.

The most powerful Zen practice is that of seeking simplicity and restraint by subtracting clutter from one’s experience, and by focusing attention in a singular way. In his 2011 article in Rotman Magazine, author Matthew May describes how the Zen principles of koko (austerity) and kanso (simplicity) can inform the work of product designers. May maintains that design is more about what you leave out of the product.

The most powerful Zen practice is that of seeking simplicity and restraint by subtracting clutter from one’s experience, and by focusing attention in a singular way. In his 2011 article in Rotman Magazine, author Matthew May describes how the Zen principles of koko (austerity) and kanso (simplicity) can inform the work of product designers. May maintains that design is more about what you leave out of the product.